Author Archives: bartswindow

1 February, 2012 13:45

Front forks for frame elements

What do you want from your bike cart?

What would you do with a bike cart if you had one? If you’re reading this blog, you’ve no doubt thought about it. You’ve probably checked out what’s available at the bike shops, and box stores, or perused the internet. Maybe you’ve even tried one or two out. Ohio City Bicyle Coop has several types for rent, if you haven’t tried one and would like to.

Do you just want to go grocery shopping, or take the kids, dog, Cello, to the park? Are you an urban farmer, without a truck, who needs to get compost seed etc to the garden, and produce to the market. Do you provide a service where your stuff could be transported by bicycle, if you could just figure out a way to load it all on? There is really no limit to what you can do with human power. Even hills, weight, and distance can be dealt with by either gearing down and taking your time, or adding another person or electric assist.

So if you had the ultimate cart for you bicycle, what would it look like what could it do? How much weight do you want to carry? What kind of doors, and gates, does it need to fit through? Does it have to ride in an elevator? Are you going to need to carry it sometimes? Does it have to be weather resistant? How quickly do you need to connect it, and disconnect it, from the bicycle. Are you going to stay on paved roads or does it need to be tough enough for cobbles, dirt, or gravel?

This is a lot of questions, all of them are important, and you could answer them one or two at a time, by buying something and finding out what’s not going to work. I’m going to try to address these issues from the perspective of someone who’s been hauling stuff around on bikes for quite a while. I’ll present a lot of examples of how other people are using bike carts. I’m also going to explore what’s available off the shelf that might fit your needs. Then I’m going to ask you to tell me what you think. I’ll attach a comment area at the end for a place to open a dialogue on this subject. If you already know what you want you could just skip this read, but you might find something here you haven’t considered.

Lets start with the basics.

geometry1 link to pdf of above drawing

Safety:

How much weight can you safely get moving and stop?

A bicycle powered by a human can pull a lot more weight than it should, if you haven’t improved the brakes on the bike, or put brakes on trailer. The momentum of the loaded trailer can push you right through an intersection, or in to a curb, car, etc. Bicycles are designed with brakes capable of stopping the vehicle, in a reasonable distance, only when they aren’t overloaded. Even with disk brakes your still limited as to how much momentum you can deal with, there is only so much rubber in contact with the road. The higher the payload the more momentum. This I think is why most trailers have around a 100 lb payload capacity. You can put a lot more weight than that, on even most of the really flimsy trailers. That doesn’t mean you should.

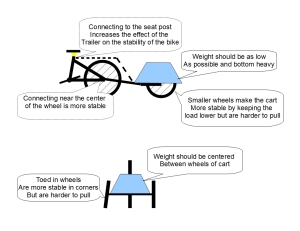

Center of gravity.

That’s the axis around which a load tends to rotate. Things that are top heavy, more weight above this pivot point then below, will tend to tip over, especially while turning or on an uneven surface. Even the best designed trailer can be loaded poorly and tip over. The majority of the weight has to sit as close to the ground as possible.

This drawing shows some considerations when loading the trailer, connecting it to the frame and alignment of wheels

The distance between the wheels of the trailer.

The greater the distance between the wheels, side to side, of a 2 or 4 wheel trailer, the more stable it will be. Being able to spread the load out over a wider area allows you to lower the center of gravity. If the load sits outside the wheel it can pull the cart over using the point where that wheel contacts the road as a pivot point.

Containment of the load. What you are hauling should not be able to contact the wheels, the road, or the tongue of the trailer. Fingers and toes, loose items, tarps, etc, should not be able to get caught in the spokes or touch any other part of the wheel. Cargo shouldn’t be able to drop under the the bottom of the trailer, and touch the road, or an obstacle in the road. The load will tend to shift around and settle on a rough surface.

Connection to the bicycle. Where, and how, you connect the trailer to the bicycle, has a lot to do with how the trailer effects the stability of the bicycle. The higher this connection point, the more force the trailer can exert, and the easier it is for the trailer to push the bicycle over when turning a corner or swerving to miss an obstacle. Mounting down near the center of the rear wheel of the bike puts it at a point below the bikes center of gravity which decreases the likely hood of the trailer taking control of the bike.

Think about what your going to be hauling and how it’s going to effect the stability of the trailer and the bicycle.

The hitch is a critical part of the trailer bike assembly. When a trailer is 2 wheeled, the hitch has to allow for turns and uneven surfaces, in order to keep all the wheels on the road. The drawing below illustrates this.

Those are some of the basics having to do with the stability and safety of the cart. I’ll show some carts that are available, and how folks are using them, in future posts.

Some things just don’t work

I tried everything I could think of to make the tongue with the split steel rims work. I bolted them in 4 or 5 places, put in a second connecting point to the main frame, and then took the brackets from a bolt on kick stand, and clamped it around the tongue and cross brace. It still had too much flex and when Jim grasped it at the cross brace and the end of the tongue he was able to easily bend the tongue upward.

I tried everything I could think of to make the tongue with the split steel rims work. I bolted them in 4 or 5 places, put in a second connecting point to the main frame, and then took the brackets from a bolt on kick stand, and clamped it around the tongue and cross brace. It still had too much flex and when Jim grasped it at the cross brace and the end of the tongue he was able to easily bend the tongue upward.

I will try using wider, stiffer alloy rims, at Stewart’s suggestion. I like the shape, it has lots of clearance for the wheel of the bike during turns, and it would be light weight. But if its not strong enough to handle the loads, then it just won’t work.

We are also going to try something that Jim had suggested, and Kevin brought up again, which is using the down tube and seat tube from a step through frame. This will be a lot stiffer, a little heavier, but may end up answering some other design needs. The problem it may present is, will there be enough clearance for the rear wheel when turning in a tight circle? There are a lot of step through frame styles and some will no doubt work better then others.

Fortunately, there are a lot of under appreciated step through frames out there. A lot of folks would call this frame design a “girls” bike and don’t want one. The truth of the matter is a step through frame has a lot of advantages over a diamond frame, Easier to get on and off, no top tube to fall on to, and a kind of built in suspension.

The process continues, some things will work, some won’t, the trick is to have the patience to work it through and to try everything you can come up with to solve the problems as they present themselves. If it doesn’t work, don’t throw away your notes, you might come across some idea that makes it work. If you take the time to review what you’ve done in the past, that didn’t work, you won’t have to go through the process again.

An Existing Prototype

Here are pictures of a cart that I made out of an old

Coos Bay Flier ( originally designed by Don Harse) style recumbent trike I had built in Cleveland.

This Cart proved itself reliable and useful in a variety of difficult terrains.

I suggest that this design be adapted to utilize the rear triangles from old bicycle frames and standard bicycle wheels instead of the cantilevered Phil Wood hubs that are used in the existing cart. Although the cantilevered wheel design is simpler, the wheels will be harder to find and costly if we have to purchase them.

I suggest that this design be adapted to utilize the rear triangles from old bicycle frames and standard bicycle wheels instead of the cantilevered Phil Wood hubs that are used in the existing cart. Although the cantilevered wheel design is simpler, the wheels will be harder to find and costly if we have to purchase them.